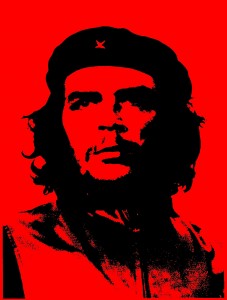

Though I’d certainly have denied it at the time, my infatuation with Che Guevara, indeed the world’s infatuation with him, had little to do with his political philosophy and everything to do with his dreamboat looks. Had Che been born with a face like Zero Mostel’s, none of us, aside from a handful of scholars and maybe the Castro brothers, would have any idea who the guy was. Further, had Alberto Korda, the man responsible for snapping the photo that would launch a billion T-shirts, called in sick that day, or if something else had caught his attention at that exact moment (“Hey Alberto, check out that sunset!”), an entire sector of the economy would have died in the womb.

Be that as it may, in 1972 Che Guevara and Jimi Hendrix, both dead but more popular than ever, shared a wall of my disgusting, clothing-strew, bong-water-soaked, third floor bedroom. From there they gazed down on me as I slept, smoked pot, masturbated, and plotted to bring down the Nixon Administration. There was no eye contact—Jimi was focused entirely on his upside-down Stratocaster, while Che had eyes only for the horizon, presumably because that’s where world revolution lurked. Lest you think smoking pot and masturbating were incompatible with bringing down the Nixon Administration, I can assure you, you are wrong. True, Che would likely have had a hard time reconciling Jimi’s sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll with the disciplined guerilla tactics that led to his triumphant entrance into Havana, looking very snazzy atop a Sherman tank. But, as he was to learn some years later in what turned out to be a suicide mission to Bolivia, every culture has its own unique path to revolution. Or, to work masturbation back into the equation, different strokes for different folks.

The bedroom just below mine belonged to my older brother John, who at that time was toking his way across Europe and North Africa with my sister Amy, my hippie Aunt Carla and her two-year old son. The previous summer Carla had somehow persuaded my parents that a year spent touring the great cultural capitals of Europe with her, an art historian, would do much more to broaden their children’s horizons than wasting it with the rest of the juniors and seniors at Cleveland Heights High School. She was right of course, though not in the way my parents had bargained for. Dad in particular was pretty upset when the postcards of the Louvre and the Sistine Chapel petered out, then stopped altogether, just after the one postmarked “Maroc” arrived. That country hadn’t been on the original itinerary, nor had my parents imagined my sister’s knowledge of French being put to use bartering for bricks of hashish in the Marrakesh Bazaar. (Amy’s skill at these negotiations so impressed the merchants there that my brother was approached by some who wondered if he’d be interested in swapping her for two hundred camels. “I considered it,” he said later, “but I wasn’t sure Cleveland Heights was zoned for that many camels.”) Needless to say, there was some serious hand wringing going on back on East Monmouth Road.

Like all little brothers with big brothers, I wanted to be just like mine. There’s nothing I would have loved more than to have disappeared into a haze of dope smoke in Morocco. But at fourteen I was deemed too young to have my horizon’s broadened, at least not in such exotic locales. Try as I might I could never hope to keep pace with brother’s drug consumption. In one area though I was able to not only go toe to toe with John, but to actually surpass him, if only in my own mind. For while John, who was about to turn eighteen and thus become eligible for the draft, had been involved in the anti-war movement (if you consider carving peace symbols out of wood and attending peace rallies involvement), I did him one better. “Fuck peace,” was my credo. “Give me revolution!”

You might think the opportunities for a young revolutionary in the suburbs of Cleveland would have been limited at that time. You would be mistaken. One such opportunity was called the Youth Against War and Fascism, “Yawf” to those in the know, a small band of Marxist thugs devoted to the overthrow of the United States government and its replacement by some vaguely Maoist alternative. To be honest, I was a lot more focused on the overthrow part than the replacement part. I particularly liked to imagine myself atop a Sherman tank, red flag and hair flapping in the breeze, rolling up to the principal’s window at Roxboro Junior High. If I couldn’t lose my virginity after that, man, I was hopeless.

I was introduced to Yawf by John Morris, a kind of surrogate older brother with long, fiery red hair, who lived across the street from Roxboro but attended the senior high school a few miles away. I used to go over to John’s house after school and smoke dope before heading out to do my evening paper route.

(A brief note about my brief career as a paperboy. I hated delivering The Cleveland Press. What could be more demeaning than being made an unwilling tool of The Man’s propaganda machine? Especially since he only paid three cents a paper! I only took it, six months earlier, because my parents insisted I start earning money to pay off my vandalism bill—it’s a long story but suffice it to say a few friends and I got the bright idea of jump starting the revolution in Cleveland Heights with the use of a BB gun and a slingshot . As with pretty much all my bright, illegal ideas, I got caught. My parents demanded I get a job—outrageous!—but they’d been doing that for a long time so I felt pretty safe. That is until my mother bumped into someone at Heinen’s whom she knew from her old PTA days and learned from her about the scandal that had resulted in a bunch of paperboys from our neighborhood being fired en masse. Apparently, for the last five years these boys had been stuffing down the storm sewer all the paid inserts they were supposed to be stuffing into the newspapers, a system that worked like a charm until a big storm came along and five years’ worth of inserts came floating out onto South Taylor Road. Next thing I knew I was handed a newspaper bag, a bundle of papers, and assigned a route of half a dozen blocks. We replacement paperboys also threw out our inserts—it’s doubtful any of these supermarket circulars ever reached their intended targets—but, having learned from the mistakes of our martyred forefathers, we avoided the sewers and instead dumped them in a ditch behind The Church of the Redeemer, conveniently located on the same corner where our bundles were dropped every afternoon.)

John Morris and I liked to get stoned and talk about how great everything would be “come the revolution.” Our pipe dreams were frequently interrupted though by John’s older brother Robert, a security guard (or “rent-a-pig,” as John called him), whom I at first took to be mildly retarded but, I don’t know, maybe it was just his speech impediment (I mean, would they really issue a retarded guy a firearm?).

“Up against the wa-wa-wa-wa-wall, motherfuh-fuh-fucker!” he said, standing in the doorway of John’s bedroom, still wearing his uniform from the morning shift.

“The FUCK do you want, Robert?” John would shout irately.

“Hey, John,” Robert said, as usual sounding as if he’d stuffed twenty packs of bubble gum into his mouth. “Wha-wha-what’s this?” he said, holding up what looked like a three-fingered variation on the peace sign. “Pah-pah-pah-pah-peace, with a little pi-pi-pi-pi-piece on the side!” at which point he dropped his hand to his holstered service revolver. A barrage of spitty guffaws followed.

“Hey Robert, what’s this?” John would say, saluting his brother with his middle finger. And round and round they went.

One thing I particularly liked about Yawf was the colorful banners they carried at demonstrations (“demos”). Unlike other groups, whose signs and banners were made out of old sheets and cardboard, ours were fashioned from silky rayon in pleasing pastel pinks, oranges, and baby blues. Ours had catchy proclamations— “Nixon: Stop Your Imperialist War Against The People of Cambodia!” “Self-Determination For Palestine!” “Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird: You Are a War Criminal!”—that were meticulously hand-lettered in black and gold paint. (Yawfers liked to say that the really great thing about their banners was how quickly they could slide the poles out of them if they had to do battle with “fascist pigs.” It’s a safe bet though that were we ever confronted by actual fascists we’d have dropped those poles and high-tailed it out of there as fast as our little Marxist legs would carry us.) Yawf also specialized in colorful chants like “Hey pig, ya better start shakin’ cuz today’s pig is tomorrow’s bacon!” They even reworked a Christmas carol, the only verse of which I can recall was “We are now a fighting movement, Fa-la-la-la-la, La-la-la-la.”

Marxism wasn’t all fun and games though, serious Yawfers frowned on dope smoking and the sort of general hedonism that was central to my strategy for bringing down the powers that be in hopelessly bourgeois Cleveland Heights. So John and I had to tone it down a bit when we went to official meetings, which were pretty tedious compared to the unofficial ones—which were often accompanied by very loud music—that we had in his bedroom (Side note: John was a rabid fan of albino blues guitarist Johnny Winter and his air guitar cover of Winter’s cover of “Highway 61 Revisited” was unquestionably the best in Northeast Ohio).

The most serious Yawfer I ever met was John’s classmate Robbie. Robbie had short blond hair and a wisp of fuzz above his upper lip. Above the fuzz was a pug nose on which was set a serious pair of coke bottle wire-rims, the better to stare at you the way a scientist might stare at a single cell organism under a microscope. Whenever you smelled of pot or laughed too hard at something other than the fate of all those imperialist running dogs come the revolution, Robbie gave you “The Stare.” I got it pretty much round the clock. It was clear that as far as Robbie was concerned Yawf was no place for a little shit from junior high school. The best I could hope for was a conditional membership, though what conditions I was required to meet was never made clear to me.

What was clear was that things weren’t going so well between Robbie and me. I’d made the mistake of assuming that as long as I looked the part of a revolutionary I would be accepted as one. But apparently that was part of the problem because one time, when I showed up at a demo wearing a black beret, my trusty little Che button affixed to the lapel of my army jacket as always, Robbie said “This isn’t a goddamn Halloween party. We mean to overthrow the government of the United States.”

Hey, I was cool with that, but where was it written you couldn’t do it with a little style?

Robbie was a big reader, especially of the movement’s foundational texts: The Communist Manifesto, Mao’s “Little Red Book,” and of course, the biggest and baddest book of all, Marx’s Das Kapital. I was relieved to discover when I first checked the Manifesto out of the library that it was under a hundred pages—piece a cake! What I didn’t realize was a little Marx went a long, long way, just half a teaspoon of the stuff was as dense as a black hole and capable of rendering even the most artificially stimulated reader instantly unconscious. Whereas The Quotations of Chairman Mao (which, due to heavy subsidizing by the Chinese Communist Party, was available in a waterproof pocket edition, complete with built-in bookmark, for only a buck at your neighborhood radical bookstore) was loaded with nifty quotes like “Every communist must grasp the truth, political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” (a Yawf favorite), it was near impossible to lift any line out of Marx without taking a whole page or two with it. (Years later, I made the mistake of assuming that my earlier difficulty with Marx had been due to intellectual immaturity and, now that I was a junior at Bard College—and no longer smoking pot or dropping acid—I was ready to wade back in with both feet. I have almost no memory of “Marxist Thought and Analysis,” a three-hour class that was unwisely scheduled for just after lunch, no doubt because I spent most of it in varying states of unconsciousness.)

Of course, if The Communist Manifesto is the Mercury space capsule of political texts, Das Kapital is surely the Death Star of economic ones (think The Hobbit vs. Lord of the Rings if you prefer, only with all the excitement—and hobbits—stripped out of it). So far as I knew, no one actually read Das Kapital (the title had to be said in German and pronounced “Dahs Kop-ee-TAHL”), at most they just kept it on a bookshelf, somewhere between Webster’s and The World Book Encyclopedia, or, like me, checked it out of the library and used it as a prop to impress girls and teachers (I had a sizable collection of books in this category, including Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and The Kitab-i-agdas, the holy book of the Baha’i faith). No one but Robbie that is.

“Enjoying the book?” he said, the day I made the mistake of showing up at John’s house carrying Volume Two, never anticipating Robbie might be there lying in wait for bourgeois posers.

“Uh huh,” I said, cautiously.

“Volume Two…hmm. So I guess you’ve already been through the whole private ownership of the means of production by the bourgeoisie part, huh?”

Nervous laugh. “Yeah.”

Robbie, his mouth smiling but his pitiless eyes locked in “The Stare,” said, “Didn’t you just love all that stuff about the commodification of labor and the devaluation of the proletariat to the status of wage slaves?”

“Yeah, that was great,” I said quietly, looking down at my feet, anything to avoid the withering power of “The Stare.”

To say this contest resembled a wounded water buffalo being circled by hyenas is to make it sound like a much fairer fight. I was more like a quadriplegic mole, helpless and blind, being casually batted around by a bored house cat. At least John, who was busy going at it with his brother upstairs, (JOHN: “Blow me!” ROBERT: “Whi-whi-whi-whip it out fu-fu-fu-fuck-f-f-f-face!”), wasn’t there to witness my humiliation.

Okay, I hadn’t read Das Kapital, not a word of it, not even the jacket notes, but it’s not like I was illiterate. I HAD read some respectable revolutionary texts. Maybe not Marx or Lenin, but how about Abbie Hoffman (Steal This Book!), Jerry Rubin (If It Feels Good Do It), and Eldridge Cleaver (Soul on Ice)? Those guys were revolutionaries, right? And what about Che Guevara? You can’t get more revolutionary than that!

“A tactician, nothing more,” Robbie had said dismissively the first time I tried impressing him with my Che talk. “Unless you’re fighting a guerilla war in a jungle somewhere he’s basically useless.”

Well, he hadn’t been useless to me the previous summer, at Unitarian church camp.

A good natured competition had developed between my cabin, Hickory, and one of the other cabins, Cedar Center, which culminated in an epic water balloon fight. It was a fight in which we got annihilated (i.e., very wet). The reason was simple, Cedar Center was twice the size, and therefore had twice the number of combatants, as Hickory. To make matters worse, we foolishly agreed to stage the battle in the field in front of Cedar Center, which meant they had their own private water source while we were limited to what we could carry. When we ran out of ammunition—er, water balloons—they swept in for the kill. When they ran out of water balloons they switched to pots and pans, which they filled in their bathroom. But here they made the mistake so common among the lopsidedly victorious: they overplayed their hand. They committed atrocities. It started when they began filling their pots and pans with hot water (not molten lead hot—there weren’t any third degree burns—but hot enough to making getting doused a particularly uncomfortable experience). But what really stung was the extra ingredient they added, an ingredient too diabolical and disgusting for us to have even imagined before we heard the anguished cry of one of our fallen comrades: “It’s PISS! They’re throwing PISS!”

Up to that point the most likely end to this bloodbath would have been for us to admit defeat and retreat to our cabin to lick our wounds (or towel off, anyway). But, as is so often the case when atrocities are committed (think My Lai, think Srebrenica), the incident merely galvanized our resolve. Revenge would be ours, no matter the cost.

Early the next morning I hitched a ride into nearby Yellow Springs, home to lefty liberal arts school, Antioch (where else would you find a shop in rural Ohio, nestled between the hardware store and the five-and-dime, with a name like “Big Bill Haywood’s Radical Book Collective”?). There I purchased a copy of Che Guevara’s Guerilla Warfare and that night, from my perch on the top bunk, I drilled my troops in the fundamentals of insurgency.

“A small, mobile force can defeat a far larger one by employing the element of surprise, striking hard and striking fast, and just as quickly disappearing into the jungle,” I said, paraphrasing my hero.

“Avoid civilians casualties at all costs; an insurgency cannot succeed without the goodwill of the populace.”

“Whenever possible, avoid engaging the common foot soldier, instead target his leaders.”

“Always hit the enemy when he least expects it. Strike terror into his heart, make sure he spends every hour of every day looking over his shoulder.”

There was also a lot of cool stuff in there about building tank traps and converting shotguns into Molotov cocktail launchers but we decided we’d stick with water balloons for the time being.

That night after dinner three of us staked out the path that ran through the woods between the dining hall and Cedar Center. It didn’t take long before Big Jim, Weasel, and Ferret—the code names we’d given the enemy’s top brass—came wandering down the trail. Right into our trap. The most satisfying thing was the look on their faces when we sprang from the woods (Weasel and Ferret in particular looked as if they’d each just dropped a load in their pants). Pelting them with water balloons was simply the icing on the cake, as was our shout of “Hickory!” as we melted back into the woods. These ambushes would repeat themselves many times over the next few days as we caught the three of them—sometimes together, sometimes singly, sometimes in the presence of females they hoped to impress—as well as a few other prominent members of the Cedar Center clan in various places about the camp, from the canoe house and the arts and crafts center, to the public latrines, whose stalls we turned into death traps (well, water balloon traps anyway.) With each attack, the legend of Hickory’s notorious guerilla band grew to become part of Unitarian folklore.

I like to think Che, looking down from atheist heaven, would have been very proud of us, for though we may not have exactly struck terror into the hearts of our enemies, we certainly had them looking over their shoulders.

“Wait, so you think because you read a few chapters of Guerilla Warfare and wear that little Che button you’re a revolutionary?” Robbie said. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed but Cleveland isn’t surrounded by jungles. And we’re not going to bring down the Nixon Administration by the arming peasants and setting a few booby traps.”

“What are we going to bring it down with then?” I said, doing my best to steer the conversation away from Das Kapital.

He shrugged. “Getting our message out? Some good old fashioned propaganda?” Then, like a Siamese grown bored with its mangled plaything, Robbie was gone.

Three days later, when I picked up my bundle of newspapers, dumping the inserts in their usual spot, I decided to replace them with some flyers John had asked me to hand out around Roxboro. Instead of the weekly specials from Heinen’s and Shop-Rite, these advertised an antiwar demonstration the following day downtown in Public Square. They were printed on bright pink paper and featured a Vietcong woman, clad in black pajamas and outfitted with a coolie hat and an AK-47. Above her, in bold letters, the headline screamed “Total Victory to the Indochinese People!!!” I had a hundred and fifty of them, just enough to cover all the houses on my route.

Less than an hour after I returned home from delivering my papers the phone rang. It was Mr. Burns, a nice old gentleman on my route whom I used to stop and chat with from time to time (he was a veteran of Iwo Jima and I enjoyed hearing his stories about it).

“Paul,” he said. “Did you put any inserts in today’s paper?”

“Inserts?”

“Yes, pink ones.”

“Not that I recall,” I said, opting for vagueness rather than the principled stand I’d imagined myself taking.

“Well, I found communist propaganda in mine and I checked with the Lawrences next door and they found the same thing in theirs.”

“Gosh, come to think of it, I noticed someone had tampered with my bundle when I picked it up today.”

“I assumed as much,” Mr. Burns said gravely. “I called the FBI.”

I lost my job with The Cleveland Press (Mr. Burns may have been gullible enough to buy the tampered bundle story, Mr. Cox, my supervisor, was not). If there was an upside to it it’s that I finally won Robbie’s respect. Next time I saw him, at the demonstration downtown, he said nothing, just walked up to me and gave me the soul brother handshake. It was without question the biggest moment of my short-lived career as a revolutionary.

No one else congratulated me. I was in some very deep shit in fact. Mr. Burns really did call the FBI and they really did call my parents (the agent seemed a lot more amused by the incident than alarmed by it, though, between that and the letter I wrote to Castro the year before asking for autographed Che pictures, one could safely assume—or dearly hope in my case—that J. Edgar Hoover had a file with my name on it). Needless to say, I wasn’t very popular around the house that fall. Things were about to change in ways I hadn’t imagined though, because what really cooked my goose was the envelope bearing the return address of Roxboro Junior High School that dropped through the mail slot a month later. It was my report card, and it was about to have me banished to Siberia.