I don’t know why they called it the Paper Sale, it’s not like they were selling anything. Every fall they would come around with their wagons and pick up all the newspapers and magazines people had socked away in their basements and garages. A year’s worth of bundles tied neatly with twine. By “they” I mean the sixth grade boys who knocked on your door and said, “Paper sale!” (They said it the way a ballpark vendor might say “HOT-dogs!,” with the emphasis on the first syllable.) Dad would have brought the bundles up from the basement the night before and stacked them in the front hall. The paper sale boy would then pick them up by the twine, a bundle in each hand, and carry them to his wagon. If he was good—most of them were good—his wagon would be stacked high with bundles from other houses. It was a wonder they never tumbled over but they never did. Not a one. When he was done he’d wait in the vestibule while my mother went in search of her purse. I would stand just inside and stare at him, fascinated. He would give me a bored, mildly contemptuous look, if he acknowledged me at all. He was a sixth grader and I was in the third grade, beneath him in every sense of the word. Following The Code of the Paper Sale Boy, he never broke his cool, not even when my mother gave him a quarter—most people never gave them a tip of any kind. About the biggest reaction you’d get was a small nod or a quiet “Thank you, ma’am.” It was clear he could take or leave your money. My mom might get a slightly bigger response if she handed him a Kennedy half dollar and you’d think he’d let out an involuntary yelp if he got one of those silver dollars some of the boys were rumored to have gotten. I’m not certain of that though. These paper sale kids were cool customers.

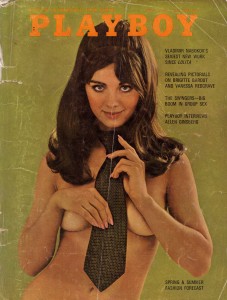

Up and down the block, boys—always boys, never girls—pulled wagons filled with bundles, steadily making their way east to west. I’m not sure how it was decided which boys would take which houses but I’m certain it was by some secret code. When his wagon was full the paper sale boy would unload it into the back of a station wagon, probably driven by someone’s father. Once full, the station wagon would speed down the road to the Church of the Savior’s parking lot, where other sixth graders would unload it and toss the bundles onto mountains of other bundles, some higher than a two-story house. The station wagon would then speed back up the road for the next load. The boys manning those mountains of bundles were preparing them for the big trucks that would soon arrive and cart them away to the recycling plant. Except for what they made in tips, the boys were never paid for their back breaking labor. And yet the people who organized the paper sale were never short of volunteers, in fact they had to turn away a fair number of them every year. What motivated these sixth graders? Was it a strong sense of civic duty? A desire to conserve the planet’s precious forests? No. It was the Playboys.

The ratio of Playboys to newspapers was something like one in seven tons. Pretty lousy odds but ones that any ten-year old boy would happily accept. There was gold to be had in those mountains of newsprint if you were willing to work for it. Every parking lot had two or three boys working the piles. Multiply that by every pile in every church, synagogue, and school parking lot across town—all of Cleveland Heights was disgorging its newspapers and magazines on that day—and you had a lot of boys working a lot of piles. Still, that was nothing compared to the number of boys crisscrossing town with their wagons. Working the piles was the more desirable job, for while the wagon boys had first crack at the bundles, the ones on the piles almost always came out on top by virtue of the sheer volume they were dealing with. Not to mention, when you spot contraband in a pile it’s a lot easier to discretely open the bundle (virtually every kid carried a standard issue Boy Scout pocket knife) and spirit away a girlie magazine than it is if you’re out there on the sidewalk for all the neighborhood to see. Which is why every kid on a wagon wanted to be upgraded to parking lot duty and why it was about as likely as winning the drawing for the gas-powered car FAO Schwartz gave away every Christmas. It wasn’t impossible—every year some kid got strep or had his grandmother die suddenly (and inconveniently). But most boys would sooner work the pile on a broken leg than give up their spot.

Just about every paper sale boy could count on coming away with at least one or two Playboys that day. There were no guarantees though and everyone had heard stories like that of Doug Leary who, though he got to work the paper sale two years in a row because he flunked sixth grade (some said he deliberately flunked for that reason), still came up empty-handed. Not a boob, not a butt, not even a see-through nightie. Apparently that second year, when he was working the Fairfax lot, Doug became so desperate as the day wore on that he worked himself into a frenzy, tearing through the piles, throwing bundles left and right, looking for something, anything, even that little bit of cleavage they put on Cosmopolitan covers. Finally the other kids working the pile took pity on him and agreed to give up some of their pictures so he got at least something for his trouble. This was more about self interest than altruism; they knew that if Doug didn’t calm down it was only a matter of time before he drew the attention of an adult. And Doug—the big baby—would almost certainly spill the beans. If word got out about the Playboys the whole operation would be compromised and years of tradition would go down the drain.

But for every Doug Leary there was a Cartie Donahoe, the wagon boy who scored the perfect bundle on his very first house. Twelve Playboys bound together with twine. They’d put a Newsweek on top but Playboys have a unique binding and Cartie knew instantly what he had. He waited until he found a good hedge and stashed the bundle, then went back for it at the end of the day. You couldn’t have asked for a better haul: twelve centerfolds and more than eighty pages of naked women, including the much prized “Girls of the Riviera.” His story was told on playgrounds and around campfires for years to come.

The paper sale was held on a Saturday but the real action began on Monday, when the school became one giant swap meet. But the sorting began even before the last bundle was carted away. All across town, in basements, tree forts, attics, and behind locked bedroom doors, far from the prying eyes of parents and little brothers and sisters, sixth graders were busily dismembering magazines and categorizing pages according to quality and value.

There were three distinct nudie sections in every Playboy. The most valuable section was the second, or middle section, because that was the one that contained the centerfold. Even if you weren’t entirely thrilled with that month’s Playmate you simply couldn’t beat a centerfold. (One caveat: the value of a centerfold was significantly reduced in those rare circumstances where the fold happened to fall on a nipple. When you encountered that all you could do was shake your head in disbelief and hope heads were rolling back at Playboy International in Chicago.)

Next in value was the third, or last, section of the magazine. This was the photo essay: “The Girls of Holland,” “Ivy League Ladies,” “California Dreamin’,” etc. There was a hierarchy within these too; “The Girls of Paris” would fetch more than “The Girls of the PAC Ten,” not because the subjects were any prettier but because they were from France, where it was assumed sexual appetites ran large (The Girl Who Puts Out always trumps The Girl Nextdoor). Any page could be moved to the top of the pile though if it had a standout photo; a girl with particularly large breasts, say, or in a position that came dangerously close to revealing more than Playboy’s policies (and perhaps the law’s) would allow. Some kids swore that if you used a magnifying glass you could actually see one or two pubic hairs, which was nonsense of course. If that were true the magazine would be wrapped in brown paper and relegated to the back of the store with the old men in trench coats. (Tangentially, I remember as if it were yesterday the day Playboy broke the pubic hair barrier. I and a half dozen of my friends were puffing on a bong in Andy Wolpert’s rec room when Buzzy Calhoun came in waving a magazine—it was April 1973 and on the cover was a girl in a form-fitting tie-dye tank top flashing the peace sign. “The new Playboy has pubes!” Buzzy said, breathlessly. “The new Playboy has pubes!” It was clear to all of us that a milestone had been passed.)

In the “C” pile were pictures from the first section of the magazine. This section showcased consumer products: men’s fashions, sports cars, high-end stereo systems. Stuff guys liked. It was the least valuable of the photo sections because the pickings were pretty slim. You were lucky if you found one or two shots of a woman hanging on a man or draped over a car and even then you probably only got some cleavage (and as far as we were concerned a boob without a nipple was like vanilla ice cream without Hershey’s on top). About the only reason the first section of a Playboy wasn’t considered a complete disappointment was that you knew the best sections were still to come. Being teased isn’t so bad when you know there’ll eventually be a payoff.

Lastly, every paper sale boy had an “everything else” pile. No photos, just racy cartoons like “Little Annie Fannie” or The Vargas Girl. The Vargas Girls were of low value not only because they were illustrations rather than photographs but because they were old fashioned, the kind of thing they used to paint on the sides of B-17s. They looked even more outdated as the years went by and Mr. Vargas (I picture an elderly Spaniard, very dignified, sitting at his easel in a coat and tie) attempted to make them more contemporary. You knew the end was near when he did that one with the naked black girl with the big afro and headband sprawled across a bed—post coital one can only assume—with the caption “Oh, so that’s what right-on means!” Still, I would take a Vargas Girl over Little Annie Fannie any day of the week.

When Monday arrived every boy got to school bright and early. He’d scrimped and saved all year for the day the paper sale boys arrived with their booty-filled book bags. Generally speaking, it wasn’t money he’d been saving but goods, this being mostly a trade only economy. But some sixth graders accepted cash, sometimes even from those lowlifes who showed up with orange “Trick or treat for UNICEF!” boxes, chock full of nickels and dimes. (My guess is many of these boys grew up to be embezzlers, Internet scammers, and corporate CEOs). The older kids—fifth graders, and sixth graders who hadn’t participated in the paper sale, —always had the best stuff to trade: airplane models still sealed in their boxes, G.I. Joes, matchbox cars (this was the pre-Hot Wheels era), those extra large army men they sold at Woolworth’s (of these the German throwing the “potato masher” was the most prized), even BB guns. It was said that Dix Brown actually traded his little brother’s Huffy for a dozen centerfolds. Talk about low.

As the week wore on the quality of the material declined and by the time we second and third graders got a crack at it they were down to the dregs. Let’s face it, seven or eight year olds don’t have much to trade, at least not much of what a sixth grader wants. With that in mind, Robbie Kubek, who lived five houses down from me, and I decided to pool our resources. Together we might be able to put together something worth trading. A paper sale boy who lived on the next block agreed to meet us behind Robbie’s garage. Robbie and I arrived ten minutes ahead of schedule. A cold snap had also arrived early and we tried to stay warm by stamping our feet and blowing on our hands. By the time the sixth grader showed up—fifteen minutes late—you could hear our teeth chattering. He made no apologies for his tardiness, clearly we were lucky he was even willing to take time out of his busy schedule to meet with us.

The kid was all business. “What’ve you got?” he said. Robbie pulled out a wind-up toy, a music box shaped like a transistor radio that played “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” The sixth grader grimaced. “What else?”

I produced a model of a jet fighter I had stolen from my brother’s closet earlier that day. Half its wing had been burned off and a line bullet holes were tattooed across its fuselage. The effect had probably been created using a blowtorch and a hot nail. This didn’t diminish its value, it increased it. The sixth grader, like all sixth graders, played it cool but I could tell from the almost imperceptible rise of an eyebrow that the plane had captured his interest. And why not? Not only had it been shot up (which meant you could spend hours with it simulating death spirals and making crashing noises) but, most important of all, it was obviously done using fire, the most forbidden substance known to grade schoolers. I would be in deep, deep trouble when my brother discovered it missing but it was late in the week and the stock of Playboys was dwindling fast. What choice did I have?

“Is that it?”

Robbie hesitated. “Wait a minute, I’ll be right back!”

I tried making small talk till Robbie got back, just to keep the kid interested, but he ignored me. What could a third grader possibly say that a sixth grader would be the least bit interested in? Finally Robbie came back huffing and puffing and tossed a dozen tiny airplanes—the kind you could buy at Sanford’s Library for a penny a piece—on the ground next to the model and the wind-up toy. Hardly worth running to the house, I thought.

The boy got down on his hanuches and examined the objects, picking up each one, turning it over, then setting it aside, silently calculating its value. Finally he stood up. “Not much to work with here,” he said, then pulled a folder out of his book bag and started rifling through some dog-earred pages. Most of it was crap, I could see that, but I caught a flash of what looked to be a “Girls of…” page (“Chicago?” “California?” I couldn’t tell). But when I leaned forward he shot me a look that said Are you kidding? and continued leafing through his inventory. He paused over some of Dempsey’s nudist colony cartoons and I thought No way, those are even worse than Little Annie Fannie! He went through a few more pages, then stopped. After a moment he pulled out a page and laid it on the ground next to the burned fighter jet, the wind-up toy, and the tiny planes.

“This is the best I can do.”

The photo was from one of those consumer goods sections (from the “C” pile), this one apparently featuring swimwear. It was an underwater shot, taken in a swimming pool (it had that telltale bluish cast), and the girl was modeling a topless bathing suit. You couldn’t really see her face, everything above water was obscured, but you could see her boobs. And what nice boobs they were. Unlike most of the pictures in this section of the magazine this one was a full page. There was no guy in there hogging the center of the frame either. And it wasn’t shot from one of those weird angles where all you got was half a boob. Two boobs, two nipples—it was all there.

“Just the one?” I said, pushing my luck.

“Take it or leave it.”

“But there are two of us,” Robbie said.

“Look, I’m doing you a favor taking this nursery school crap off your hands,” the sixth grader said, pointing to Robbie’s wind-up toy. He started to put the page back in his bag. “But if you’d rather…”

“No! We’ll definitely take it!” I said.

After the paper sale boy left I had a momentary twinge of buyer’s remorse. That burned fighter plane was pretty cool and I’d basically given it up for a piece of paper. I was going to take a major pounding from my brother when he discovered it was gone. But when I looked at those boobs floating there in that otherworldly blue light my regrets evaporated. They were well worth a pounding. The only thing that needed resolving now was how Robbie and I would share custody. We decided we’d alternate days. We flipped a coin to see who got it first and I won.